Herbs and Medicine in Ancient Egyptian Art Ancient Egyptian Art New Kingdom

Introduction

When studying the history of medicine, names such as the Greek physicians Hippocrates (circa 460–circa 375 BCE) and Galen (129 CE–circa 216 CE) immediately come up to listen. Modern medicine is indebted to the ancient Greeks, but information technology is equally important to study the development of medicine in the ancient About E before the Hellenistic catamenia. As this section volition demonstrate, we are just as indebted to the ancient Egyptians as we are to the Greeks.

Medicine in ancient Egypt incorporated both conventional (rational) medicine and religious practices. Organized religion played a major role in ancient Egyptian daily life. There was an overlap between the priesthood and healers in add-on to the frequent employment of incantations, amulets, and imagery related to deities such as Horus and Seth.[1] The Egyptians' religious life and views helped shape their understanding of the human being trunk, how it functions, and how to heal it.

Aboriginal Egyptians recognized health and affliction every bit expressions of an private's relationship with the world, which comprised people, animals, spirits, and gods.[two] Although they saw a distinction between the mundane/mortal and the supernatural/divine, they saw these worlds as frequently interacting with one another. Maat (guild, rest, justice) was an integral part of this, governing people'south actions and approaches to healing illnesses and injuries (fig. 1).

Figure 1. Scarab inscribed for Maatkare (Hatshepsut), New Kingdom, Eighteenth Dynasty (1479–1458 BCE). In the center of the base of the scarab in the cartouche is Hatshepsut's throne name, Maatkare (Hatshepsut was queen and later pharaoh during the Eighteenth Dynasty). Maatkare mostly translates as "Maat is the life force of Re (the sun god)." On either side of the cartouche are feathers representing the goddess Maat (truth). To a higher place the cartouche is a winged sun disk and beneath is a wide collar with falcon terminals. Steatite (glazed), 1.eight × one.3 cm (11/16 × 1/two in.). New York Metropolitan Fine art Museum, Rogers Fund, 1927, 27.3.230.

Figure 1. Scarab inscribed for Maatkare (Hatshepsut), New Kingdom, Eighteenth Dynasty (1479–1458 BCE). In the center of the base of the scarab in the cartouche is Hatshepsut's throne name, Maatkare (Hatshepsut was queen and later pharaoh during the Eighteenth Dynasty). Maatkare mostly translates as "Maat is the life force of Re (the sun god)." On either side of the cartouche are feathers representing the goddess Maat (truth). To a higher place the cartouche is a winged sun disk and beneath is a wide collar with falcon terminals. Steatite (glazed), 1.eight × one.3 cm (11/16 × 1/two in.). New York Metropolitan Fine art Museum, Rogers Fund, 1927, 27.3.230.

One's good health meant that maat was balanced, while illness, injuries, and other issues indicated that maat was not in social club. Health depended on this balance merely like Egypt depended on the Nile River to maintain life.[three] Purity preserved maat and thus the torso guided views on the relationship between the mortal world and the divine. Being pure was particularly important when one was coming into contact with the divine, including priests. To non exist then could anger the gods.[iv] The swnw (conventionally pronounced equally "sewnew"), wab priest, and sau were healers who focused either on the divine or mortal aspects of an illness or injury.[5] They turned to the religious idea that affliction was a bulletin from divine entities with access to heka (magic power). Symptoms were a effect of a disturbance of maat, which could exist repaired by heka, supplication, spells, and ritual.[6]

Much of what we know about ancient Egyptian medicine comes from human remains, visual representation as seen in tombs and temples, amidst other places, and through written texts. The get-go of organized medical care and the development of Egyptian medical science may exist credited to Imhotep, during the reign of Pharaoh Djoser of the Third Dynasty (circa 2686–2613, Old Kingdom). Clemens of Alexandria (150–215 CE) noted that this noesis may have existed much earlier with Athothis of the First Dynasty (circa 3100–2890); (son of Menes, the first pharaoh and who united Upper and Lower Arab republic of egypt) and who may take authored a volume on anatomy.[seven]

The Corpus of Medical Papyri

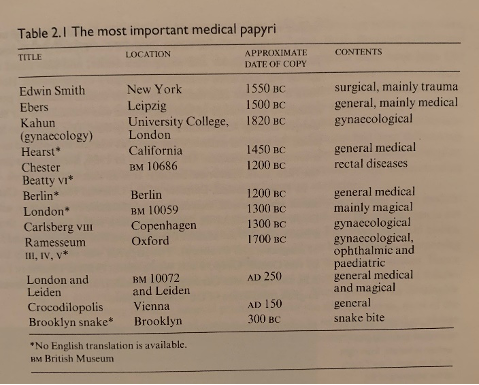

Much of what we know about aboriginal Egyptian medicine has been preserved through several medical papyri. Many of the surviving papyri accept been found in tombs. Before the discovery of these papyri, much of what we knew was through the writings of individuals similar Hippocrates, Homer, Herodotus, Pliny the Elder, and Diodorus.[viii] Although the papyri are in various states of preservation, they give us valuable insight into the ancient Egyptians' knowledge of human being anatomy and physiology, ways of diagnosing disease and injuries, and how to treat medical bug using both rational medicine and magico-religious (a belief in supernatural beings) elements. Presently, in that location are at least eleven known medical texts (in chronological order): the Kahun, Ramesseum, Edwin Smith, Ebers, Berlin, Hearst, London, Chester Beatty, Carlsberg, Brooklyn, and the London-Leiden Papyrus (fig. 2).[ix]

Figure two. List of significant ancient Egyptian medical papyri. From John F. Nunn, Ancient Egyptian Medicine (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1996).

All of these papyri were composed in hieratic except Ramesseum 5, which is in cursive hieroglyphs, much like the Kahun veterinary text. Later papyri were equanimous mainly in demotic, which was the dominant script.[x] Hieratic and cursive hieroglyphs were used at the same time and within a medical setting. Thus, they may have been understood by nigh physicians. Hieratic is a cursive course of Egyptian hieroglyphs that could be written quickly on papyri for administrative and literary purposes, while cursive hieroglyphs were used mainly in religious texts (including the Book of the Dead). Demotic was primarily used for administrative purposes only over time too came to be used for literary, science, and religious documents.[11] There is no clear reason why the Ramesseum V and the Kahun texts were written in a dissimilar script than the other texts. There is reason to believe that we only have a fraction of medical papyri that existed, as some papyri quote or allude to unknown texts.[12]

Some papyri appear to have been handbooks for physicians, while others have outlines from lectures, tape instructions including lecture notes, or were clinical notebooks owned past students.[13] Many only provide remedies for diseases, list numerous drugs bachelor simply without including much other information. These drugs are likely to accept been from local plants, minerals, and animals, but some may too have been imported, such equally lapis lazuli from Afghanistan.[14] A few of the papyri that incorporate magic explain their origins in order to institute authorization and authenticity, in certain cases stating that they were establish at the human foot of a statue of a god.[fifteen] Although many of the texts take been successfully translated, there is still much that is unknown. Some of the vocabulary just occurs in the medical texts, while other words are well known in nonmedical settings just have specific unknown meanings in the medical context.[16]

The Edwin Smith and Ebers Papyri are the almost well-known and informative of all the medical papyri, giving a structured method of budgeted patient diagnosis and handling. Both were purchased in 1862 by the American Edwin Smith, who lived in Luxor, Egypt, from 1858–1876 (the Ebers Papyrus was afterwards purchased by Georg Ebers in 1872). They may accept come up from the same tomb, that of a physician cached in the Theban necropolis on the west bank of the Nile.[17] The Edwin Smith Papyrus dates to circa 1600 BCE (late Centre Kingdom), with most of the language beingness in Middle Egyptian. Information technology is generally agreed, however, that the original dates to the Old Kingdom (ca. 2600–2500 BCE). This papyrus stands out for its content and approach to medicine, and is often referred to as the surgical papyrus. It focuses on 40-eight cases of more often than not traumatic injuries and treatments of the caput, face, cervix, upper part of the thorax, spine, and arm.[eighteen] Information technology follows empirical agreement, is an education volume rather than just a compilation of remedies, and only has one spell. Each medical instance follows the same blueprint, beginning with the championship "knowledge gained from practical experience: examination, diagnosis and prognosis, and treatment."[19] Physical manipulations, sutures, and bandages are the primary means of treatment of injuries that were likely caused by diverse types of weapons.[20]

Over time, the Edwin Smith Papyrus became i of the standard reference texts on treating trauma in ancient Arab republic of egypt and the glosses that were added to fill in omissions attest to its continual utilization.[21] If the Edwin Smith Papyrus is equally old as some scholars believe, information technology contains the earliest known examination of the pulse and details the parallel roles of the medico, the priest of Sekhmet, and magicians. Some scholars advise that the papyrus contains the offset clarification of the circulation of blood. If this is true it means that there was some understanding of this long earlier the Greek Democritus' own description in his treatise On Nutrition.[22] After Smith'south expiry the papyrus was donated to the New York Historical Guild and in 1920 the papyrus was given to Egyptologist James Henry Breasted for translation. After a lengthy period of written report and analysis, Breasted translated the papyrus. In 1930, he published a historic two-volume edition containing the English translation, with medical notes prepared by physician Arno Luckhardt and an hieroglyphic transcription of the original coil.

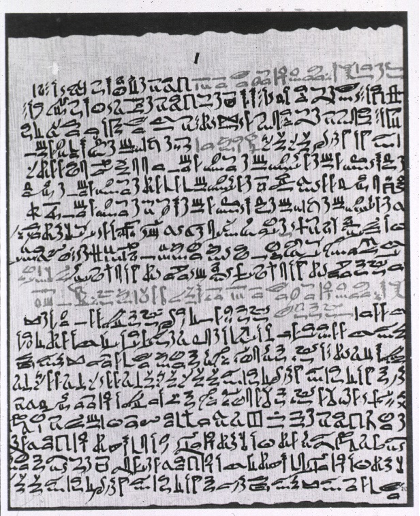

The Ebers Papyrus (circa 1550 BCE) is the longest medical text and is in very good condition (fig. 3).

Figure three. A department from the Ebers Papyrus (circa 1550 BCE). From the National Library of Medicine at the U.S. National Plant of Health, http://resource.nlm.nih.gov/101436767.

This text is a compilation of original medical texts haphazardly ordered, which makes deciphering references to ailments and treatments difficult, just it nonetheless presents us with a latitude of information. Paragraph 856a notes that the original text was "'establish among writings of ancient times in chests of writing material under the feet of Anubis, in Letopolis, in the time of the majesty of the king of Upper and Lower Egypt Den' (First Dynasty)."[23] This gave the text added ancient authority in its own time (the Berlin Papyrus makes the aforementioned statement), every bit the god Anubis possessed medical noesis and was patron of embalmers. Unlike the Edwin Smith Papyrus, diseases or symptoms are oft assumed, and so only a treatment or remedy is listed. Medical issues addressed in this text include those related to the stomach (15 diseases); the anus; the peel (18 diseases); a pregnant section focuses on the eye (29 diseases); and 21 treatments are provided for cough.[24] There is also a notable section called The Book of Vessels, which focuses on the metu. The metu is more often than not identified every bit the blood vessels, ducts, tendons, muscles, and possibly the fretfulness, although it is uncertain how well the ancient Egyptians understood the nervous system. The metu may send blood, air, fungus, semen, urine, and illness, acting as canals for substances to flow through. The pulse was taken regularly to make sure the metu vessels were open.[25] The terminate of the text is more than surgical in nature and is our main source on surgery exterior of trauma, listing about 700 drugs and 800 formulas.[26] At that place are several spells in the text and there are parallels with the Hearst, Berlin, and London papyri.[27]

Another noteworthy medical text is the Kahun gynecological papyrus. This papyrus was found past Flinders Petrie in 1889 in the Fayum expanse. It dates to circa 1850–1825 BCE, during Amenemhat III'southward reign, and is written in hieratic, although the accompanying veterinarian text is in hieroglyphic script, which is usually reserved for religious texts. Information technology is in very poor condition, but nonetheless gives us insight into ancient Egyptian's notions of gynecological issues, including contraception and pregnancy testing. The information does not relate to current gynecological understanding and in that location is zero about obstetrics or midwives. Along with this text, there are substantial sections of the Berlin, Carlsberg, Ebers, London, and Ramesseum papyri that address gynecological concerns.[28]

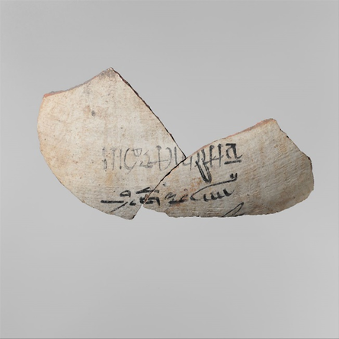

In addition to writing medical cognition on papyri, physicians as well wrote on ostraca, which are potsherds or flakes of mostly white limestone. Due to the cloth used, ostraca terminal longer than papyri. Known medical ostraca engagement from the Amarna Catamenia (Eighteenth Dynasty) to the Roman occupation (30 BCE–395 CE).[29] Medical ostraca were likely used to transmit knowledge and collect treatments in texts. Frequently, medical treatments were listed 1 afterward another on these. In general, ostraca were easy to carry and were disposable. As a issue, there are probably many medical ostraca missing. Unfortunately, nosotros do not know who specifically used ostraca, whether all physicians did or only physicians of certain levels.

The Medical Profession

While the pharaoh was seen as the supreme healer, his powers were delegated to physicians, priests of Sekhmet and Serqet, and magicians who played disquisitional roles in the process of diagnosing and treating injuries and diseases. Oftentimes these roles were intertwined with 1 other, with some individuals having one or more of these positions. Physicians came from various social classes and the title of md was held in high regard.

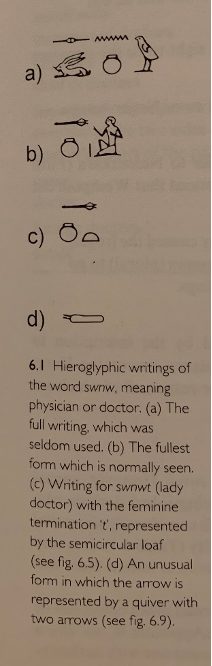

Swnw is usually the ancient Egyptian term translated as dr. or physician (fig. 4).

| Figure 4. Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphic variations of the word swnw. From John F. Nunn, Aboriginal Egyptian Medicine (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1996). |  |

This title appears 150 times in tomb biographies, graffiti, stelae, and papyri dating from the Fourth Dynasty (2649–2513 BC) to the Twenty-seventh Dynasty (525–404 BCE). This is linguistically similar to the Egyptian give-and-take for pain (swny.t) and for affliction (swn).[30] One of the identifying features of the swnw in the medical papyri is the phrase "placing the paw."[31] This may take been a way of diagnosing and/or was similar to "the laying on of hands" every bit we say today every bit a means of healing.[32] After the Twenty-seventh Dynasty, when Egypt came nether Farsi rule, swnw came to mean both doctor and embalmer.[33] Furthermore, during the Ptolemaic Period, swnw could mean embalmer also.[34] Previously, during the Pharaonic menstruation, in that location may have been limited interactions betwixt physicians and embalmers. Egyptologist Kent Weeks recommends that a more than accurate translation of swnw should exist "one who treats the ailments of the upper classes," which reflects the idea that nigh swnw had connections with the royal courtroom rather than treating ordinary people.[35]

Wab (pure) priests and sau (magicians) were additional healers who used similar healing techniques as swnw. Wab priests and sau are mentioned in the Edwin Smith and Ebers papyri equally placing their hand over a patient, demonstrating their participation in healing traumatic injuries and internal ailments. The championship wab tin refer to even the most novice temple personnel. In the medical context, the title is normally, "wab priest of Sekhmet." The lioness goddess Sekhmet was both a destructive and healing force. Sau is often translated as magician, just some scholars suggest that a better translation is "protector" or "amulet-man," although the latter may non be completely accurate either as information technology implies that the sau simply worked with amulets, which is non the case. Sau is often used in connection with Serqet, the scorpion goddess. Like Sekhmet, this goddess also embodied destructive and healing aspects.[36]

The Court medico formed the apex of the medical field.[37] In the Old Kingdom, nigh half of the known doctors and dentists had royal connections. After the Old Kingdom the number of known doctors with a royal connectedness becomes much fewer. Several swnw too had a priestly title, such as wab priest of Sekhmet, hem netjer (servant of god), or wab nesu (royal priest). Additionally, some swnw were appointed to estates of gods, including that of Amun and Ptah, as well as the "Place of Truth" (the necropolis). [38] Selected physicians were sent to treat miners, workmen, or soldiers, or else were temple physicians, who were at the lowest level of the social ladder and fabricated firm visits.[39] Physicians often associated themselves with deities who related to their specialties.[forty]

Physician Titles

While most physicians had the championship swnw, at that place were other known related titles, including kherep swnw, meaning the about exalted "controller or administrator of doctors." Hery swnw and imy-r hateful "1 with authorisation over doctors" and "overseer," respectively, while sehedj or shd swnw is translated as "inspector." The senior physician was referred to as "Overseer of the House of Health" or "Primary of the House of Secrets," and smsw swnw meant the "eldest of doctors."[1] The most widely held special championship was wr swnw, meaning "great one" or "primary" physician. Sometimes titles were followed past the geographic limitation of authority, such as Upper or Lower Egypt or both. Many physicians served pharaoh, frequently having the championship swnw per aa, significant "doctor of the Keen Firm or palace."

Documents suggest that, much like in mod medicine, ancient Egyptian doctors had specialties.[41] For case, Herodotus famously recorded in his travels to Arab republic of egypt in about 450 BCE that "medicine is practiced among them on a programme of separation; each physician treats a unmarried disorder, and no more than: thus, the land swarms with medical practitioners, some undertaking to cure diseases of the heart, others of the head, others again of the teeth, others of the intestines, and some of those which are not local."[42] This sentiment is supported past qualifying words relating to body parts post-obit swnw, which have been found on several stelae.[43] In addition, a number of doctors noted that they were besides scribes, and some doctors were as well dentists. It has been argued that swnw was primarily a physician while surgeons may have been referred to as "smashing ones of the body" and were mainly wab priests of Sekhmet.[44]

Physicians received years of training at the Peri-Ankh, or "House of Life," which was either within or attached to a temple and also served every bit a scriptorium and library where chief copies of papyri were likely held.[45] Medicine was a specialty inside scribal instruction.[46] Surgeons received special rudimentary training. It was a science and known as early on as 4000 BCE, although the first record of surgical procedures was as early as 2500 BCE.[47] In addition, information technology appears, based on the papyri, that all physicians were expected to have basic knowledge of all types of medication available.[48] There is indication that medical wisdom was passed down through families, every bit institute on stelae apropos Khay and Huy also as being documented in the Ebers Papyrus in an obscure passage.[49]

Like other parts of the ancient Near Eastward, such as Mesopotamia, Egypt's political structure meant that the medical field was well organized, although in that location was no medical licensure organisation.[fifty] Physicians were required to follow strict rules of handling. One reason for this was that information technology was deemed that there was nothing to amend upon the existing wisdom of older eras. Physicians were advised to use but the authoritative texts and methods so that their actions would be beyond question.[51] After, Aristotle wrote that physicians were "warned by the country non to alter a grade of treatment until at to the lowest degree four days have passed, or else exist subject to legal penalties."[52] For example, if the physician deviated within those four days he risked the penalisation of death if the patient died.

Based on the evidence nosotros take, almost 150 physicians are attested to from the Old Kingdom to the Late Period.[53] A few notable physicians are Djer; Imhotep; Amenhotep, son of Hapu; Netjer-hotep; Hesy-ra; Pesehet; Mereuka; Ankh; Ir-en-akhty; Gua and Seni; Renef-seneb; Hery-shef-nakht; Wedja-hor-resnet; Iry; and Pentu. Imhotep ("he who comes in peace") is mayhap the well-nigh well-known (fig. 5).

Figure 5. Statuette of Imhotep, donated by Padisu, Late Period-Ptolemaic Period (circa 664–30 BCE). Cupreous (copper-containing) metallic, 17.nine cm × 5.iv cm × 12.9 cm (seven 1/xvi × 2 1/eight × 5 ane/xvi in.). New York Metropolitan Museum of Art, Theodore M. Davis Drove, Bequest of Theodore One thousand. Davis, 1915, 30.eight.94.

Figure 5. Statuette of Imhotep, donated by Padisu, Late Period-Ptolemaic Period (circa 664–30 BCE). Cupreous (copper-containing) metallic, 17.nine cm × 5.iv cm × 12.9 cm (seven 1/xvi × 2 1/eight × 5 ane/xvi in.). New York Metropolitan Museum of Art, Theodore M. Davis Drove, Bequest of Theodore One thousand. Davis, 1915, 30.eight.94.

He was the regal chamberlain of Pharaoh Djoser of the Third Dynasty and was architect of the Step Pyramid in addition to being a priest, astrologer, and sage. Possibly by the Nineteenth Dynasty (circa 1295–1186 BCE, New Kingdom) and certainly past the Twenty-seventh Dynasty (circa 525–404 BCE, Western farsi Dynasty), Imhotep was deified as the "son of Ptah," later replacing Thoth every bit the main god of healing.[54] He was the merely not-royal to exist deified.[55] Miniature statues of Imhotep were sometimes worn as amulets to protect confronting illness.[56] During the Ptolemaic Menstruation Imhotep was often identified with Asklepios, the ancient Greek god of medicine, but information technology is not apparent if Imhotep ever held the title swnw.[57]

Hesy-ra, a gimmicky of Imhotep, is considered the get-go documented medico in the globe (circa 2650 BCE), working during Djoser's reign. He held several titles, including wer ibeh swnw, "chief of dentists and doctors."[58] Co-ordinate to a stela plant in Akhet-hotep'southward Fifth or Sixth Dynasty tomb (circa 2494–2181 BCE, Onetime Kingdom), Pesehet is perhaps the first female doctor, or at least the first female overseer, of doctors. She held the titles imy-r swnwt, which could be read "[female] overseer of the female doctors," and imy-r hem-ka, "overseer of the funerary priest."[59] While she held the championship of overseer, this does not necessarily hateful she was a medico herself. Pesehet remains the only attested female physician in ancient Egypt.[60] Hery-shef-nakht of the Twelfth Dynasty (circa 1985–1795 BCE, Heart Kingdom) uniquely held triple qualification as wer swnw, wab priest of Sekhmet, and overseer of magicians. These titles were recorded in the Ebers Papyrus. He also held the important title wer swnw n nesu, chief of the rex's physicians.[61] Iri, a 6th Dynasty doctor, was referred to every bit the Keeper of the Royal Rectum and "one understanding the internal liquids" and was possibly the pharaoh's enema proficient.[62]

Ancient Egyptian physicians were well known in neighboring countries. They were regularly requested by the Hittite court.[63] For case, Rameses II was asked to send a physician to the Hittite court "to prepare herbs for Karunta, Male monarch of the land of Tarhuntas," according to an Akkadian text well-nigh Pariamakhu.[64] Egyptian doctors were sent to dislodge a possessing demon, to heal the Hittite king's eye, and "to provide the male monarch's vassals 'with all sorts of prescriptions.'"[65] Rameses 2 also wrote, "They volition bring to you all the very practiced remedies which are here in Egypt, and which I allowed in friendly fashion to go to y'all in order to help you."[66] Some other request was made in which Neb-amen, a New Kingdom physician, received gifts for assisting a Syrian prince. Homer's Odyssey besides references ancient Egyptian medicine, and Herodotus remarked that before the Persian invasion, Male monarch Cyrus sent items to Pharaoh Ahmose II (Amasis) "for the services of the best ophthalmologist in Arab republic of egypt."[67] Strange physicians were besides allowed to practice medicine in Egypt, equally indicated by four Babylonian physicians in New Kingdom records.[68] The Greeks expressed admiration for Egyptian medicine, specifically the effectiveness of their drugs.[69] In turn, at that place is evidence that Egyptian physicians adopted medical concepts from contact with peoples in the Levant, most notably during the Eighteenth Dynasty and the Ramesside Period (Nineteenth Dynasty). For example, the Nineteenth Dynasty London Medical Papyrus incorporates seven incantations in two different languages; six are in Northwest Semitic dialects and written in syllabic Egyptian script, while i is in the Cretan language, using syllabic Egyptian script. These prescriptions were accustomed into Egyptian medical practice every bit legitimate remedies rather than existence marginalized. Some other example is a Cretan spell confronting an "Asiatic illness" using an Egyptian methodology from the Eighteenth Dynasty Hearst Medical Papyrus to treat the disquiet.[seventy]

Ailments, Injuries, and Treatments

Snake and scorpion bites, heart diseases, and gastrointestinal problems were among the most oftentimes treated ailments. Pneumonia and silicosis (inhaling grit particles), parasitic diseases, typhoid, dysentery, smallpox, and diarrhea were other common ailments.[71] Although they believed that people were born healthy, ancient Egyptians believed that their well-being was endangered by both earthly and supernatural forces, such as through intestinal putrefaction or cancerous deities inbound through actual openings and consuming vital parts of the interior of the body. Supernatural origins of disease "could function as a form of penalisation from the gods, a reminder of one's social obligation or an outright attack by a malicious or arbitrary entity."[72] Peculiarly unpleasant remedies sometimes were prescribed that were intended to rid the body of a malignant spirit.[73] Expert health was linked with living correctly, which included being at peace with the gods and spirits, as well as the deceased.[74] It was thought that illness was due to an imbalance that could subsequently be brought back to equilibrium through prayers, spells, and rituals.

It is articulate from the Edwin Smith and Ebers papyri that the ancient Egyptians had a rudimentary understanding of the cardiovascular organisation, seeing this as a network of vessels (metu) coming from the eye and going through the torso to the organs and other trunk parts. The heart was the center of the organisation, where "the metu delivered and received."[75] This system involved the movement throughout the body of air, h2o, blood, and bodily waste, termed every bit wekhedu. Wekhedu was a distinct focus of the aboriginal Egyptians.[76] The accumulation of actual waste sometimes appeared as pus in wounds or blisters as wekhedu worked through the blood system. Physicians sought to treat this past keeping wounds make clean and bandaged with dear and copper salts. Physicians advocated purging one's body and using enemas and emetics in order to keep wekhedu from accumulating. Enemas had a divine origin equally ancient Egyptians believed that Thoth invented them.[77]

It is evident from the Edwin Smith Papyrus that the brain was the location "of the nervous control of the body" and that paralysis could exist considering of a encephalon injury.[78] The ancient Egyptians had an extensive knowledge about the skull, encephalon, jaw, and face, in particular. This was due in role to traumatic injuries that often occurred from industrial accidents, warfare, or beast bites.[79] Fractures were frequent injuries. Consequently, the Egyptians had an extensive set of words describing various types of fractures, including more complicated ones.[80]

In terms of treatment, it was ofttimes stated in the Edwin Smith and Ebers papyri that the doctor would either treat, "fence with," or non treat.[81] The options were based on the level of the doctor'south confidence that the injury was treatable. If a patient could non be treated, he or she was still given care and kept comfortable until death.[82]

Views on the sources and nature of diseases ranged widely and medical classifications were fabricated based on symptoms rather than diseases. Traumatic injuries had an obvious origin and therefore a sure means of diagnosis and handling with some anticipated effect.

This includes the belief that objects could be infused with a life-forcefulness or spirit, allowing the object to deed against an individual, thus was the cause of the injury considering the object readjusted maat.[83] Conversely, internal issues, such as middle disease and lung ailments, had unpredictable outcomes as the source of illness was not always apparent. In these cases, reliance on incantations, spells, and amulets was mutual, sometimes in combination with drugs. If it was believed that in that location was a supernatural origin of the disease, such as a malign deity, the supernatural (benign deities) would be relied upon to cure the ailment. Many deities were invoked to prevent or cure diseases or attacks by unsafe animals.[84] Incantations often took the class of directly addressing the illness or disease-demon. Incantations or prayers were also meant to reinforce the effectiveness of remedies and oft were related to specific diseases and drugs.[85] They were infused with heka, which involved the component of speech.[86] Egyptians idea that the "divine artistic word and magical energy" could plow ideas into reality and therefore negate or turn away negative forces.[87] Often, spells or incantations had a "sympathetic" role; therefore, they would have been pragmatic and rational to the aboriginal physician.[88]

Amulets were also worn as a means of addressing wellness care. Many amulets resembled living creatures (human or animal) or specific body parts, with the intent of the wearer assimilating the desired characteristic, such as strength or sharp eyesight. A number of people also wore amulets to protect against harm, such every bit animal bites.[89] It was thought that the fabric the amulet was fabricated of and the shape of it provided protection and healing for the wearer. Even substances that came in contact with amulets were considered to have a healing upshot.[90] Amulets take been used by many people across the centuries and cultures. People still wear them today, believing that certain objects, whether they are of natural fabric or human-made, have ability from a greater forcefulness, from a religious connection, or through the way the object was created. A rabbit's human foot or other practiced-luck charms are such examples.

Prescriptions fabricated from animals, minerals, and vegetable substances were a regular ways of treating diverse types of illnesses and injuries. The ancient Egyptian pharmacopeia was quite rich, although many of the terms have non however been translated.[91] The efficacy of various drugs was not always evident, since multiple drugs were often utilized simultaneously, with several elements involved, while other times drugs were used in tandem with magic. H2o, booze (beer and wine), oil, honey, and milk were part of preparing various types of prescriptions (fig. 6).[92]

Figure 6. Pharmaceutical jar, Saite Catamenia, Xx-6th Dynasty (570–526 BCE). The inscription lists the contents of the jar as "Special ointment of the Director of the Red-Crown Enclaves and Main Physician, Harkhebi." The man who owned the jar likely lived in the town of Buto in the Nile Delta. The "Red-Crown Enclaves" was an aboriginal area in Buto. Travertine (Egyptian alabaster), 47 × 34 cm (18 i/2 × 13 3/8 in.). New York Metropolitan Fine art Museum, Rogers Fund, 1942, 42.2.2.

Drugs were administered in five ways: orally, rectally, vaginally, by external application, and past fumigation. They were given in the grade of cakes, suppositories, enemas, mouth rinses, tablets, drops, ointments, or special baths.[93] Often prescriptions would be made based on the patient'southward age and weight.[94] Physicians also recited incantations while preparing or administering prescriptions.[95]

Drugs made from animals include honey, milk, excrement, blood, urine, placenta, bile, creature fat, meat, and liver and other internal organs. Love was an specially beneficial chemical element for its antibacterial and antifungal properties, besides as being a flavorful condiment to other drugs (fig. vii).

Figure 7. Fragment of a jar with a label identifying the contents every bit love. The script is in hieratic, which is written correct to left. The sign at the first of the second line represents a bee, the symbol used for the word "honey." New Kingdom, Eighteenth Dynasty (1390–1352 BCE). Pottery and ink, viii.5 x 15.iii × 0.7 cm (three 3/8 × 6 × one/4 in.). New York Metropolitan Fine art Museum, Rogers Fund, 1917, 17.10.12.

Dearest was used both internally, including helping with cough, and externally, for various types of wounds.[96] This is the example today also. Honey is however used to help reduce coughs and sooth sore throats. It is too beneficial in healing wounds, including burns and leg ulcers, because of its antibacterial and anti-inflammatory properties. For this reason, it may besides help with skin grafts.[97] Milk was mainly used to go far easier to swallow other ingredients, although information technology was sometimes used equally an enema or applied to skin, eyes, or ears.[98] Like honey, information technology too helped with respiratory ailments and throat irritations. Animal fatty was utilized to make a greasy ointment, merely also to convey the meaningful brute characteristics, such as strength.[99] For certain wounds, applying a cast with fresh meat on the first solar day was full general practice. In subsequent days, bandages with beloved and oil or resin would be applied, which helped the healing process.

Some mineral-based drugs that were used include natron, mutual table salt, malachite, lapis lazuli, imru, and gypsum. Natron was particularly beneficial in drawing out fluid and reducing swelling and was oft practical with bandages. Malachite was the base for dark-green center paint and was often used for treating middle diseases, which were widespread due to flies, dust, and sand. Malachite is a natural antibacterial and was used in cases to treat burns or inflammation. Withal, it is unclear if the ancient Egyptians recognized this property or if they were more influenced by the decorative elements of the mineral.

The ancient Egyptians took reward of the plants and herbs available to them, including onions, mint, lettuce, barley, acacia, dates, willow, dill, aloe vera, frankincense, garlic, mustard seeds, and linseed, amidst others. Aloe vera is one plant nosotros nonetheless use to assist soothe sunburns and other skin ailments. We too mint or peppermint today to assistance with stomach bug. Unfortunately, in that location is difficulty in positively identifying some of the plant species that were used. Reasons for this are that the affliction for which the remedy was created cannot be translated or is otherwise unknown; in a few cases it is unknown which part of the plant was added, or we may not know the fullness of the pharmacological effect of the plant. Some plants may now exist extinct or take disappeared from the Nile Valley, which also hinders researchers in determining the plant species that were used.[100] Cannabis was known by the ancient Egyptians, including using hemp to make rope. Information technology infrequently appears in the medical papyri and was administered by rima oris, rectum, vagina, fumigation, on bandaged skin, and applied to the eyes. Information technology is unknown if the Egyptians understood the furnishings of the plant on the nervous system.[101] Booze was probable the customary means of alleviating pain, just as it has been used in the centuries since.

Nearly a quarter of the listed prescriptions in the Ebers Papyrus were for gastrointestinal bug. As previously commented, the bowels were a specific focus for the ancient Egyptians at all levels of society, as they believed that a certain toxin (wekhedu) originated there, which could and so spread to the residual of the body and crusade crumbling, disease, and death.[102] They skillful purging themselves on a regular ground in guild to go on their bodies healthy (Herodotus noted that this occurred for three days each month).[103] Brush oil, senna, and colocynth were often consumed for this process, while earth almonds and tiger nuts were besides regularly eaten. Wormwood and pomegranate were constructive in treating intestinal parasites.

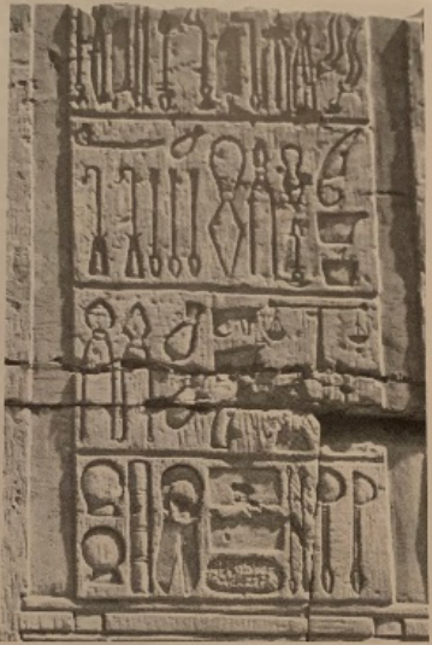

In that location currently is not much documentation of surgery beyond uncomplicated procedures including removing tumors, closing wounds, or treating traumatic injuries such as fractures. At that place are simply a few examples of homo remains that show that the ancient Egyptians knew of trephination to salvage swelling of the encephalon.[104] Wounds were often either closed with linen sutures, every bit observed in seven cases in the Edwin Smith Papyrus, or bandaged with linen.[105] Surgery deep within the body was generally non practiced because of the lack of an anesthetic.[106] Some surgical instruments referenced in the medical papyri are lancets, tweezers, drills, hook-like instruments, retractors, and dental tools (fig. 8).

Effigy eight. Image of medical instruments chiseled on the inner role of the northern section of the outer enclosure wall of the temple of Kom Ombo (Roman era). Kom Ombo is due north of Aswan in southern Arab republic of egypt. From John F. Nunn, Aboriginal Egyptian Medicine (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1996).

Statuary was initially widely implemented just subsequently copper was the preferred metal.

Snakes were much dreaded in aboriginal Arab republic of egypt. While the Edwin Smith Papyrus does not address how snake bites were treated and the Ebers Papyrus only minimally addresses this, the Brooklyn Museum Papyri focuses on this subject. The extant copy of the text dates to circa 6th-4th century BCE, although the original may date every bit early as the Old Kingdom.[107] The papyri identify at least twenty-one snakes and one chameleon. Information technology as well provides a brief description of the effects of the unlike types of serpent bites, along with the prognosis. Care included local handling of the seize with teeth, drugs (mainly herbal), and incantations. Many of these treatments intended to accost pain and swelling equally opposed to preventing the general absorption of the venom. There are several suggestions of applying bandages, which would have helped with applying localized drugs. Onion was one of the main ingredients for treating bites, which was oft role of a chemical compound with table salt and sweet beer, and at times was utilized along with incantations. Emetics were besides prescribed, as the theory was to expel the venom through vomiting. The kherep priests of Serqet were the main healers in preventing and treating ophidian bites every bit well as scorpion stings.[108]

Ancient Arab republic of egypt's Influence on Greek Medicine

Not long afterward Alexander the Dandy invaded Egypt in 332 BCE, the famous Alexandrian medical schoolhouse was established, which had a great impact during the Ptolemaic, Roman, and Coptic periods. Many Greek physicians studied there, including Herophilus and Galen. Pliny the Elder, the Roman naturalist, asserted that the art of medicine may accept been invented by the Egyptians.[109] Scholars accept long debated the extent to which the Egyptians may have influenced aboriginal Greek medicine.

The following is what some scholars merits as being amid the contributions. The Greek medico Herophilus, who studied in Alexandria, adopted the technique of pulse-taking as developed by the Egyptians. In add-on, the practice of mummification allowed for anatomical dissection, which was otherwise taboo in ancient Hellenic republic. The Pre-Alexandrian Hippocratic Corpus illustrates parallels with Egyptian ideas and practices, such as birth prognoses adapted from pregnancy texts constitute in the Kahun, Carlsberg, and Berlin papyri, likewise as disorders of the womb.[110] Some of the Greek gynecological, and perhaps surgical, techniques may also be attributed to ancient Egyptians.[111] A few Egyptian terms were also adopted into Greek, such as that for migraine.[112] The four humors in Greek thinking may have also first come from Egypt.[113]

In addition, nosotros know that the Greeks imitated and further developed the practise of empirical examination of patients, including diagnosis and prognosis.[114] The practice of incubation (sleeping in a sacred area with the purpose of experiencing divine dreams or healing) may also take originated with the Egyptians.[115] There is textual evidence that this exercise existed at Deir el-Medina during the New Kingdom, circa 1200 BCE, and that temples at Sais and Heliopolis were well-known medical centers in the Middle Kingdom, circa 1900 BCE.[116]

Ane of the most noteworthy ancient Egyptian contributions to Greek, and afterward Roman, medicine is pharmaceuticals. The symbol for prescription, Rx, is Latin for "recipe," significant "take," and may have originated from the Centre of Horus (fig. 9), which was an especially significant component of ancient Egyptian medicine, as it was believed that it had ability to heal and protect.

Figure 9. Stamp seal in the shape of Wedjat-Eye (Eye of Horus), New Kingdom, Eighteenth Dynasty (1400–1390 BCE). Steatite (glazed), i.vii × i.1 × 0.six cm (eleven/16 × vii/16 × 1/4 in.). New York Metropolitan Art Museum, gift of Helen Miller Gould, 1910, 10.130.208.

It besides served to mensurate prescriptions, as the mathematical proportions of the eye were used to decide the amount of ingredients in medicines. The center was divided into six parts related to the six senses: bear upon, taste, thought, hearing, sight, and olfactory property.[117] In improver, many drugs and vegetable substances termed "Egyptian" played a prominent role in Greek and Roman medicine, equally found in Greek medical works such as the Hippocratic Corpus and in the works of Herophilos, Dioscurides, Galen, and Pliny. The Odyssey as well refers to Helen of Troy dispensing a drug to soothe her guest, where information technology is said to have been a souvenir from an Egyptian adult female, and she praises Egyptian physicians as beingness "knowledgeable beyond all humans."[118] Pharmaceutical contributions include natron, aloe, chicory, alum, beans, castor oil, comfrey, pomegranate, saffron, and other oils and perfumes. The nearly pop was natron, as information technology is a naturally occurring soda that is used for cleansing purposes. The administration of drugs was also influenced by the Egyptians. Greek physicians at the Alexandrian medical school were the first to quantify specific ingredients in remedies, mimicking the precision of the Egyptians. One markedly influential prescription ingredient was the "milk of a woman who has borne a male child," which was "sympathetically evoking the curative milk of Isis later the birth and injury of [her son] Horus" (fig. 10).

Figure ten. Isis and the infant Horus, circa 300 BCE, Ptolemaic Kingdom (332 BCE–thirty CE). Statuary and wood, xvi.51 cm (six.v in.). Spencer Museum of Art, Academy of Kansas, gift of Dr. Franklin D. Spud, 1956.0029.

This element tin be found several times in Egyptian texts and after was recommended in the Hippocratic Corpus, by Pliny and Dioscorides, in Coptic medicine, and in British herbals from the twelfth through seventeenth centuries. Brush oil was another prescribed drug that is still used today.[119] Conversely, in later Egyptian medical papyri new drugs appear, and while they are transcribed in Egyptian, they originated from someplace else.[120]

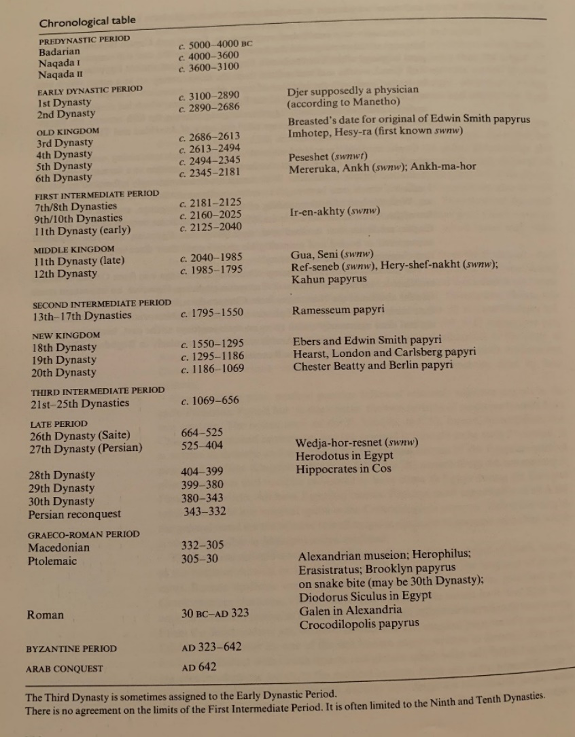

Chronology of aboriginal Egyptian dynasties, notable physicians, and medical papyri. From John F. Nunn, Aboriginal Egyptian Medicine (Norman: Academy of Oklahoma Press, 1996).

Bibliography

Aboelsoud, N. H. "Herbal Medicine in Ancient Egypt." Periodical of Medicinal Plants Research 4, no. 2 (2010): 82–86.

Allen, James P. "The Art of Medicine in Ancient Egypt." In The Fine art of Medicine in Ancient Egypt. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2005, nine–12.

Carrick, Paul. Medical Ethics in the Aboriginal World. Washington: Georgetown Academy Press, 2001.

Escolano-Poveda, Marina. "Demotic: Opening New Windows into the Understanding of Egyptian History and Culture." ARCE, American Research Middle in Egypt. October 20, 2020. https://www.arce.org/resource/demotic-opening-new-windows-understanding-egyptian-history-and-culture#:~:text=The%20term%xx%E2%80%9CDemotic%E2%lxxx%9D%20refers%20to,language%20of%20the%20New%20Kingdom.

Gross, Charles. "From Imhotep to Hubel and Wiesel: The Story of Visual Cortex." In Brain, Vision, Retention: Tales in the History of Neuroscience. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1998, 1–90.

Horstmanshoff, H. F. J., and Marten Stol, eds. Magic and Rationality in Ancient About Eastern and Graeco-Roman Medicine. Leiden: Brill, 2004.

Longrigg, James. Greek Rational Medicine: Philosophy and Medicine from Alcmaeon to the Alexandrians. London: Routledge, 1993.

Meo, Sultan Ayoub, Saleh Ahmad Al-Asiri, Abdul Latief Mahesar, and Mohammad Javed Ansari. "Function of Honey in Mod Medicine." Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences 24 no. v (2017): 975–78.

Mininberg, David T. "The Legacy of Ancient Egyptian Medicine." In The Art of Medicine in Aboriginal Egypt. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2005, 9–12.

Nicolaides, Angelo. "Assessing Medical Practice and Surgical Technology in the Egyptian Pharaonic Era." Medical Technology SA 27, no. 1 (2013): 19–25.

Nunn, John F. Ancient Egyptian Medicine. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1996.

Porter, Roy. The Greatest Do good to Mankind: A Medical History of Humanity. New York: Westward.W. Norton Co., 1997.

Ritner, Robert K. "Innovations and Adaptations in Aboriginal Egyptian Medicine." Journal of Near Eastern Studies 59, no. 2 (2000): 107–17.

Saber, Aly. "Ancient Egyptian Surgical Heritage." Journal of Investigative Surgery 23, no. 6 (2010): 327–34.

Saunders. J. B. de C. Grand. The Transitions from Aboriginal Egyptian to Greek Medicine. Lawrence, KS: University of Kansas Press, 1963.

"Snakebite Papyrus." Brooklyn Museum. https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/opencollection/objects/124173.

Sullivan, Richard. "A Cursory Journey into Medical Care and Illness in Ancient Egypt." Journal of the Imperial Club of Medicine 88, no. seven (1995): 141–45.

Zucconi, Laura M. "Medicine and Faith in Ancient Arab republic of egypt." Faith Compass 1, no. 1 (2007): 26–37.

Suggested Further Reading

Ghaliounghui, Paul. The Firm of Life: Magic and Science in Aboriginal Arab republic of egypt. 2nd ed. Amsterdam: B.M. Israël, 1973.

Ghaliounghui, Paul. The Physicians of Pharaonic Egypt. Cairo: Al-Ahram Center for Scientific Translations, 1983.

Grapow, Herman, and Hildegard von Deines. Grundriss der Medizin der Alten Ägypter. Berlin: Akademie-Verlag, 1954.

Halioua, Bruno, and Bernard Ziskind. Medicine in the Days of the Pharaohs. Trans. Grand.B. DeBevoise. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2005.

Jonckheere, Frans.Les Médicines de l'Egypte Pharaonique: Essai de Prosopographie. Brussels: Éditions de la Fondation Éqyptologique, 1958.

Laskaris, Julie. The Art Is Long: On the Sacred Illness and the Scientific Tradition. Leiden: Brill, 2002.

Lefebvre, Gustave. Essai sur la Médecine Égyptienne de l'Époque Pharaonique. Paris: Presses

Universitaires de France, 1956.

Majno, Guido. The Healing Hand: Man and Wound in the Ancient World. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Academy Press, 1975.

Manniche, Lise. An Aboriginal Egyptian Herbal. Austin: Academy of Texas Press, 1989.

Saba, Magdi Thousand., Hector O. Ventura, Mohamed Saleh, and Mandeep R. Mehra. "Aboriginal Egyptian Medicine and the Concept of Centre Failure." Journal of Cardiac Failure 12, no. 6 (2006): 416–21.

Westendorf, Wolfhart. Handbuch der altägyptischen Medizin. Leiden: Brill, 1999.

[1]. Laura M. Zucconi, "Medicine and Religion in Ancient Arab republic of egypt," Organized religion Compass i, no. one (2007): 26.

[ii]. Zucconi, "Medicine and Religion," 27.

[three]. Zucconi, "Medicine and Religion," 28.

[4]. Zucconi, "Medicine and Religion," 28.

5. John F. Nunn, Aboriginal Egyptian Medicine (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1996), 115.

[6]. Zucconi, "Medicine and Religion," 36; and Roy Porter, The Greatest Do good to Mankind: A Medical History of Humanity (New York: Westward.W. Norton Co., 1997), 49.

[7]. Richard Sullivan, "A Brief Journeying into Medical Care and Disease in Aboriginal Egypt," Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 88, no. vii (1995): 141–42.

[8]. Angelo Nicolaides, "Assessing Medical Exercise and Surgical Technology in the Egyptian Pharaonic Era," Medical Technology SA 27, no. i (2013): nineteen.

[9]. Zucconi, "Medicine and Religion," 26.

[10]. Nunn, Ancient Egyptian Medicine, 23, 24, 39.

[12]. Nunn, Aboriginal Egyptian Medicine, 24; and Robert Thou. Ritner, "Innovations and Adaptations in Ancient Egyptian Medicine," Periodical of Well-nigh Eastern Studies 59, no. 2 (2000): 108.

[13]. Rosalie David in H. F. J. Horstmanshoff and Marten Stol, eds., Magic and Rationality in Aboriginal Nigh Eastern and Graeco-Roman Medicine (Leiden: Brill, 2004), 140.

[fourteen]. Nunn, Ancient Egyptian Medicine, 138.

[fifteen]. Nunn, Aboriginal Egyptian Medicine, 104.

[16]. Nunn, Ancient Egyptian Medicine, 25, 68.

[17]. Nunn, Ancient Egyptian Medicine, xxx.

[eighteen]. James P. Allen, "The Art of Medicine in Ancient Egypt," in The Fine art of Medicine in Ancient Egypt (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2005), 11.

[19]. Nunn, Ancient Egyptian Medicine, 26–thirty; and Allen, "The Fine art of Medicine in Ancient Egypt," 9.

[20]. Zucconi, "Medicine and Organized religion," 27; and Allen, "The Art of Medicine in Ancient Arab republic of egypt," nine.

[21]. Nunn, Ancient Egyptian Medicine, 26–30.

[22]. Sullivan, "A Brief Journeying," 141.

[23]. Nunn, Aboriginal Egyptian Medicine, 31, 38; and J. B. de C. M. Saunders, The Transitions from Ancient Egyptian to Greek Medicine (Lawrence, KS: Academy of Kansas Press, 1963).

[24]. Porter, The Greatest Benefit, 48.

[25]. Zucconi, "Medicine and Religion," 28.

[26]. Porter, The Greatest Do good, 48.

[27]. The majority of the information in this paragraph comes from Nunn, Aboriginal Egyptian Medicine, 30–34.

[28]. All Information in this paragraph comes from Nunn, Ancient Egyptian Medicine, 34–35.

[29]. Nunn, Aboriginal Egyptian Medicine, 41.

[30]. Zucconi, "Medicine and Religion," 35.

[31]. Nunn, Ancient Egyptian Medicine, 115.

[32]. Nunn, Aboriginal Egyptian Medicine, 115.

[33]. Nunn, Ancient Egyptian Medicine, 115, 134.

[34]. Nunn, Ancient Egyptian Medicine, 44.

[35]. Robert Arnott in H. F. J. Horstmanshoff and Marten Stol, eds., Magic and Rationality in Ancient Virtually Eastern and Graeco-Roman Medicine (Leiden: Brill, 2004), 156n7.

[36]. Information in this paragraph from Zucconi, "Medicine and Religion," 34.

[37]. Porter, The Greatest Do good, 49.

[38]. The majority of the data in this paragraph comes from Nunn, Ancient Egyptian Medicine, 116–118, 120.

[39]. Nicolaides, "Assessing Medical Practice," 21.

[twoscore]. Sullivan, "A Brief Journeying," 142.

[41]. Nunn, Ancient Egyptian Medicine, eleven.

[42]. Paul Carrick, Medical Ethics in the Ancient World (Washington: Georgetown University Press, 2001), 15. Porter also cites a like quote; see The Greatest Do good, 49.

[43]. Nunn, Aboriginal Egyptian Medicine, 119.

[44]. Nicolaides, "Assessing Medical Practice," 20; and Nunn, Ancient Egyptian Medicine, 119.

[45]. Nicolaides, "Assessing Medical Exercise," 21; and David, Magic and Rationality, 138.

[46]. David T. Mininberg, "The Legacy of Ancient Egyptian Medicine," in The Art of Medicine in Ancient Egypt (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2005), thirteen.

[47]. Nicolaides, "Assessing Medical Do," 19, 22.

[48]. Nicolaides, "Assessing Medical Do," 21.

[49]. Nunn, Ancient Egyptian Medicine, 130–131.

[50]. Porter, The Greatest Benefit, l.

[51]. Nicolaides, "Assessing Medical Exercise," 21.

[52]. Carrick, Medical Ideals, 72.

[53]. Ritner, "Innovations and Adaptations," 116.

[54]. Nunn, Ancient Egyptian Medicine, 122; and Nicolaides, "Assessing Medical Practice," 20.

[55]. Nicolaides, "Assessing Medical Practice," 20.

[56]. Charles Gross, "From Imhotep to Hubel and Wiesel: The Story of Visual Cortex," in Brain, Vision, Retention: Tales in the History of Neuroscience (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1998), v.

[57]. Nunn, Aboriginal Egyptian Medicine, 122; and Allen, "The Art of Medicine," 12.

[58]. Nunn, Ancient Egyptian Medicine, 124.

[59]. Nunn, Ancient Egyptian Medicine, 124.

[sixty]. Ritner, "Innovations and Adaptations," 117; and Porter, The Greatest Benefit, 49.

[61]. Nunn, Ancient Egyptian Medicine, 128.

[62]. Porter, The Greatest Do good, 49; and Nicolaides, "Assessing Medical Practice," 21.

[63]. Ritner, "Innovations and Adaptations," 111; and Arnott, Magic and Rationality, 169.

[64]. Nunn, Aboriginal Egyptian Medicine, 131.

[65]. Ritner, "Innovations and Adaptations," 112.

[66]. Ritner, "Innovations and Adaptations," 112.

[67]. Nunn, Ancient Egyptian Medicine, 132; and James Longrigg, Greek Rational Medicine: Philosophy and Medicine from Alcmaeon to the Alexandrians (London: Routledge, 1993), 228n2.

[68]. Most information in this paragraph comes from Nunn, Ancient Egyptian Medicine, 131–32.

[69]. Carrick, Medical Ethics, xv.

[70]. Ritner, "Innovations and Adaptations," 111.

[71]. Nicolaides, "Assessing Medical Practice," twenty.

[72]. Zucconi, "Medicine and Religion," 20.

[73]. David, Magic and Rationality, 141.

[74]. Porter, The Greatest Benefit, 49.

[75]. Nicolaides, "Assessing Medical Practice," 21.

[76]. Ritner, "Innovations and Adaptations," 114.

[77]. Porter, The Greatest Benefit, 49.

[78]. David, Magic and Rationality, 144.

[79]. Nunn, Ancient Egyptian Medicine, 50.

[80]. Nunn, Ancient Egyptian Medicine, 57.

[81]. Nunn, Ancient Egyptian Medicine, 114.

[82]. Carrick, Medical Ethics, 74.

[83]. Zucconi, "Medicine and Religion," xxx.

[84]. Nunn, Ancient Egyptian Medicine, 96.

[85]. Nunn, Ancient Egyptian Medicine, 105.

[86]. Zucconi, "Medicine and Faith," 32.

[87]. David, Magic and Rationality, 134.

[88]. Ritner, "Innovations and Adaptations," 113.

[89]. Nunn, Ancient Egyptian Medicine, 110.

[90]. Allen, "The Art of Medicine," 10.

[91]. Nunn, Aboriginal Egyptian Medicine, 144.

[92]. Nunn, Aboriginal Egyptian Medicine, 139–twoscore.

[93]. Nicolaides, "Assessing Medical Practice," 21.

[94]. Nicolaides, "Assessing Medical Practice," 22; and N. H. Aboelsoud, "Herbal Medicine in Ancient Egypt," Journal of Medicinal Plants Research iv, no. ii (2010): 84.

[95]. Aboelsoud, "Herbal Medicine in Ancient Egypt," 82.

[96]. Nunn, Ancient Egyptian Medicine, 148.

[97]. Sultan Ayoub Meo, Saleh Ahmad Al-Asiri, Abdul Latief Mahesar, and Mohammad Javed Ansari, "Role of Honey in Modern Medicine," Saudi Periodical of Biological Sciences 24 no. v (2017): 977.

[98]. Nunn, Ancient Egyptian Medicine, 148.

[99]. Nunn, Ancient Egyptian Medicine, 149–l.

[100]. Nunn, Aboriginal Egyptian Medicine, 151.

[101]. Nunn, Aboriginal Egyptian Medicine, 156.

[102]. Nunn, Aboriginal Egyptian Medicine, 158.

[103]. Porter, The Greatest Do good, l.

[104]. Nunn, Ancient Egyptian Medicine, 169.

[105]. Nunn, Ancient Egyptian Medicine, 171 and 173; and Mininberg, "The Legacy of Ancient Egyptian Medicine," 14.

[106]. Nicolaides, "Assessing Medical Exercise," 22.

[108]. All data in this paragraph is from Nunn, Ancient Egyptian Medicine, 188–89, 99–100.

[109]. Longrigg, Greek Rational Medicine, 229n17.

[110]. Longrigg, Greek Rational Medicine, 11.

[111]. Longrigg, Greek Rational Medicine, 10.

[112]. Near information in this paragraph is from Ritner, "Innovations and Adaptations," 115–16.

[113]. Carrick, Medical Ethics, xv–16.

[114]. Carrick, Medical Ideals, xv.

[115]. Longrigg, Greek Rational Medicine, ten.

[116]. David, Magic and Rationality, 143.

[117]. Aly Saber, "Aboriginal Egyptian Surgical Heritage," Journal of Investigative Surgery 23, no. 6 (2010): 333.

[118]. Longrigg, Greek Rational Medicine, ten; and Arnott, Magic and Rationality, 183.

[119]. Much of the information in this paragraph, including the quote about milk, is from Ritner, "Innovations and Adaptations," 116.

[120]. David, Magic and Rationality, 145.

แสดงความคิดเห็น for "Herbs and Medicine in Ancient Egyptian Art Ancient Egyptian Art New Kingdom"